Liver Cysts (source: teach me surgery)

Introduction

Cystic diseases of the liver are relatively common conditions and are most commonly identified incidentally on routine imaging. However, in rare cases they can be complicated and life-threatening.

In this article, we will discuss the varying types of cystic liver disease, their investigation, and management options.

Simple Cysts

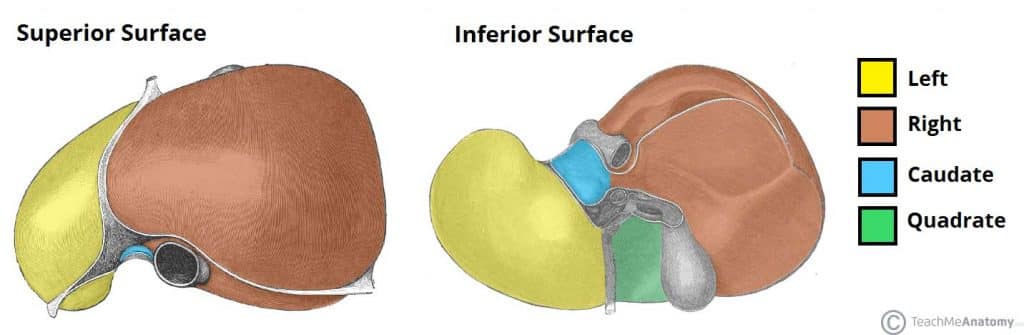

Simple liver cysts are simple fluid-filled epithelial-lined sacs within the liver, most commonly occurring in the right lobe. They are relatively common, with a prevalence of 2.5-18%, increasing in incidence with age.

They are thought to be due to congenitally malformed bile duct cells, failing to connect to the extrahepatic ducts, which leads to a local dilatation filled with a bile-like fluid, of varying size.

Clinical Features

Simple cysts are normally asymptomatic and often detected incidentally on imaging.

Around 10-15% of patients experience symptoms* such as abdominal pain, nausea, and early satiety (typically due to mass effect on surrounding structures).

*There does appear to be a correlation between increased size of cysts and increased incidence of compilations

Investigations

LFTs are typically normal, although a small number of patients may have a raised GGT. Tumour markers CEA and CA19-9 can also be elevated in some cases.

Ultrasound remains the imaging modality of choice for investigating suspected liver cysts. Simple cysts are characteristically anechoic, well-defined, thin-walled (often imperceptible), oval/spherical lesions with no septations, and strong posterior wall acoustic enhancement.

Management

Most cysts require no intervention, though for cysts >4cm in size, follow-up ultrasound scans are recommended at 3, 6 and 12 months post-detection to check for growth. If the size of the cyst remains unchanged after 2-3 years, no further scans are required unless the patient becomes symptomatic.

If the patient is symptomatic or the diagnosis is uncertain, further intervention may be warranted. Options include ultrasound-guided aspiration or laparoscopic de-roofing*, with the latter having lower rates of failure and recurrence.

*Simple cysts are often said to exhibit a characteristic “blue hue” when seen at laparoscopy

Polycystic Liver Disease

Polycystic liver disease is characterised by the presence of ≥20 cysts within the liver parenchyma, each of which are ≥1cm in size.

They are almost invariably caused by one of the two following autosomal dominant conditions:

- Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD)

- Caused by mutations in the PKD1 (chromosome 16) and PKD2 (chromosome 4) genes, whereby 10-60% of patients will also develop have liver cysts (as the most common extra-renal manifestation of ADPKD)

- Autosomal dominant polycystic liver disease (ADPLD)

- Caused by mutations in the PRKCSH (chromosome 19) or SEC63 (chromosome 6) genes; patients with this genotype will not have any renal involvement.

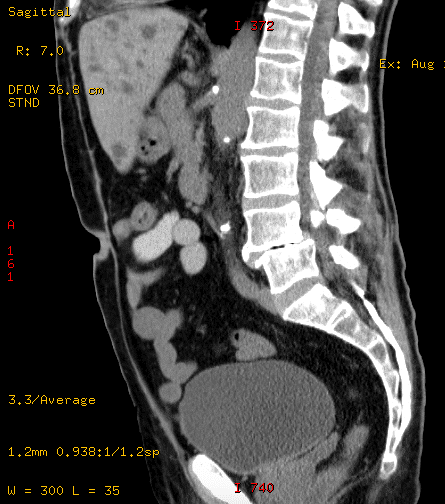

Figure 2 – A CT scan of a patient with ADPKD demonstrating multiple liver cysts present

Mutations in these genes result in aberrant ductal plate configurations during liver embryogenesis.

Importantly, these structures are not connected to the intrahepatic bile ducts and so do not drain, leading to dilatation and eventual cyst formation as they progressively fill with bile-like fluid.

Clinical Features

The majority of patients are asymptomatic, symptoms only arising as a result of localised compression or complications.

In those symptomatic, patients will often present with abdominal pain as the cysts grow in size and hepatomegaly being present on examination. Any concurrent renal disease may also present with additional urinary tract symptoms.

Significant disease can eventually cause liver cirrhosis and portal hypertension.

Investigations

Most patients will have normal LFTs (ALP can become raised in a small proportion); renal function can be affected in those with renal cysts too.

Definitive diagnosis is via ultrasound imaging, demonstrating multiple cysts, usually ≥20, which have the same sonographic characteristics as simple cysts (see above)

Management

Asymptomatic cystic disease can be left alone and monitored, though many patients will eventually require some form of intervention due to its progressive nature. Some trials have demonstrated the short-term benefit for somatostatin analogues in symptomatic relief (acting to reduce cyst volume).

Indications for surgery for cystic liver lesions are (1) intractable symptoms (2) inability to rule out malignancy on imaging alone (3) prevention of malignancy.

- US-guided aspiration may provide temporary relief in patients experiencing pain due to cyst size, although this is not routinely performed due to fluid re-accumulation

- Laparoscopic de-roofing of cysts is the preferred technique in those experiencing symptoms or for whom there is evidence of compression of surrounding structures

- Where particular liver segments are grossly affected, then resection may be preferred, and in extreme cases, transplantation may be warranted

Cystic Neoplasms

True cystic neoplasms of the liver are rare and account for <5% of liver cysts.

Most common subtype are cystadenomas (non-invasive mucinous cystic neoplasms). These are premalignant lesions, developing as a result of abnormal proliferation of biliary epithelium and can undergo malignant transformation into cystadenocarcinomas in around 10% of cases.

Clinical Features

As with other hepatic cysts, patients are commonly asymptomatic. Cystic neoplasms grow slowly, typically 1-2mm per year and if symptoms do develop, they may do so insidiously.

For symptomatic individuals, common symptoms include abdominal pain and anorexia, as well as more vague symptoms of nausea, fullness, and bloating.

Investigations

LFTs are often normal, although ALP, CEA, and CA19-9 can all become mildly elevated. Ultrasound scanning will often be able to differentiate between simple cysts and more complicated cystic lesions.

CT imaging with contrast should be performed on all patients in whom a cystic neoplasm is suspected for further delineation +/- evidence of metastasis.

Aspiration or biopsy should be avoided if a cystic neoplasm is suspected as this can result in potential peritoneal seeding of the malignancy.

Suspicious Features on Imaging

There are several features that can be seen on imaging for liver cysts that can suggest a sinister pathology:

- Suspicious for malignancy – (1) septations (2) wall enhancement (3) nodularity

- Suspicious for abscess – (1) debris within the lesion (2) Loculation (may also suggest malignancy)

- Suspicious for hydatid cyst – (1) Calcification (2) “Daughter cysts” around the main lesion

Management

Liver lobe resection is the treatment of choice for both cystadenomas and cystadenocarcinomas, with the samples only then sent for histopathology to confirm the diagnosis.

Hydatid Cysts

Hydatid cysts, or Echinococcal cysts, result from infection by the tapeworm Echinococcus granulosus.

The eggs as passed by faceo-oral transmission. After being excreted by carnivores (commonly from dogs), the larvae invade their hosts’ gastrointestinal tract, before passing via the hepatic portal system into the liver, where they continue to grow and form cysts.

Echinococcal disease has a global distribution, though the highest prevalence is in South America, North Africa and Central Asia.

Clinical Features

Cysts may only grow at a rate of a couple of millimetres per year. As a result, they can remain asymptomatic and undetected for many years.

The most common presenting symptom is vague abdominal pain, caused by mass effect on surrounding structures or due to rupture.

The disease can also result in jaundice or cholangitis (if the biliary system is involved), vomiting, dyspepsia and early satiety or rarely anaphylaxis if the cyst ruptures into the thorax or intraperitoneally.

Investigations

LFTs are often normal, unless presenting with a cholangitis picture. FBC can show an eosinophilia. Echinococcal antibody titres are positive in 80% of those with the disease.

Ultrasound scanning will reveal a calcified, spherical lesion with multiple septations. It may be anechoic or containing snowflake-like inclusions. Further assessment can be performed via CT imaging with contrast.

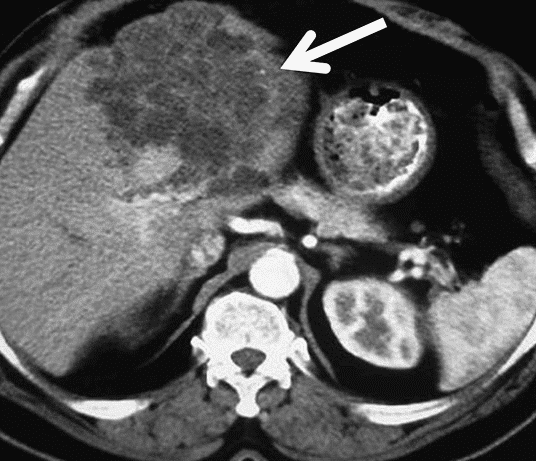

Figure 4 – CT scan demonstrating polycystic echinococcosis affecting the left side of the liver

Management

Aspiration is not recommend in those with suspected hydatid cysts as rupture may cause an anaphylactic reaction. If cysts are asymptomatic and inactive, it may be possible to monitor them.

The primary treatment is surgical with cyst deroofing. Radiological drainage and injection of scolecidal agent (the PAIR technique) is also an option in specialist centres.

Medical management is used as an adjunct to surgical therapy, in those with widely disseminated hydatid disease or in patients who are unfit for surgery. For patients in whom active treatment is indicated, anti-microbial action varies however a combination of albendazole, mebendazole and/or praziquantel is normally given.

Key Points

- Most cystic disease of the liver is asymptomatic and is identified incidentally on routine imaging

- Indications for surgery for cystic liver lesions are (1) intractable symptoms (2) inability to rule out malignancy on imaging alone (3) prevention of malignancy

- Aspiration or biopsy should be avoided if a cystic neoplasm is suspected as this can result in potential peritoneal seeding of the malignancy